About this deal

Join me for a visit to the museum storeroom, the place where curators engage with artifacts directly, thinking through the problems of exhibitions or research in a material, affective, way. A museum storeroom might be thought of as a kind of memory palace, an extension of the curator’s brain. Things are organized, available, visible on shelves or ready to be discovered behind neatly labeled cabinet doors. Museum curators have the privilege of access to the storeroom, of seeing the categories made physical, gaining a visceral understanding of how those categories came to be, what they reveal and what they hide. Storerooms highlight the materiality of objects, their heft and presence, a perfect counterbalance to the way that the registrar’s files capture their history and exhibitions their meanings. What can we learn from the materiality of the thing? “Mind in Matter,” Jules Prown’s seminal essay on material culture, calls for “sensory engagement” with the object. The material culture analyst “handles, lifts, uses, walks through, or experiments physically with the object.” What might using the thing tell us? Objects provoke affect; curators respond to them emotionally. Prown calls for “the empathetic linking of the material…world of the object with the perceiver’s world of existence and experience.” Entomology collections and staff, National Museum of Natural History. From NMNH Collections Program Photo Gallery, The new material culture studies are based on Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory. Latour wants us to consider the ways that “things” are actors, or, more precisely, what he calls “actants” — they have agency, they put human ideas into motion. He urges us to look at the heterogeneous associations of human and nonhuman actors, the relationship between people and things. Fascinating examination of the museum’s unconventional role in contemporary art....Highly recommended.”— Library Journal

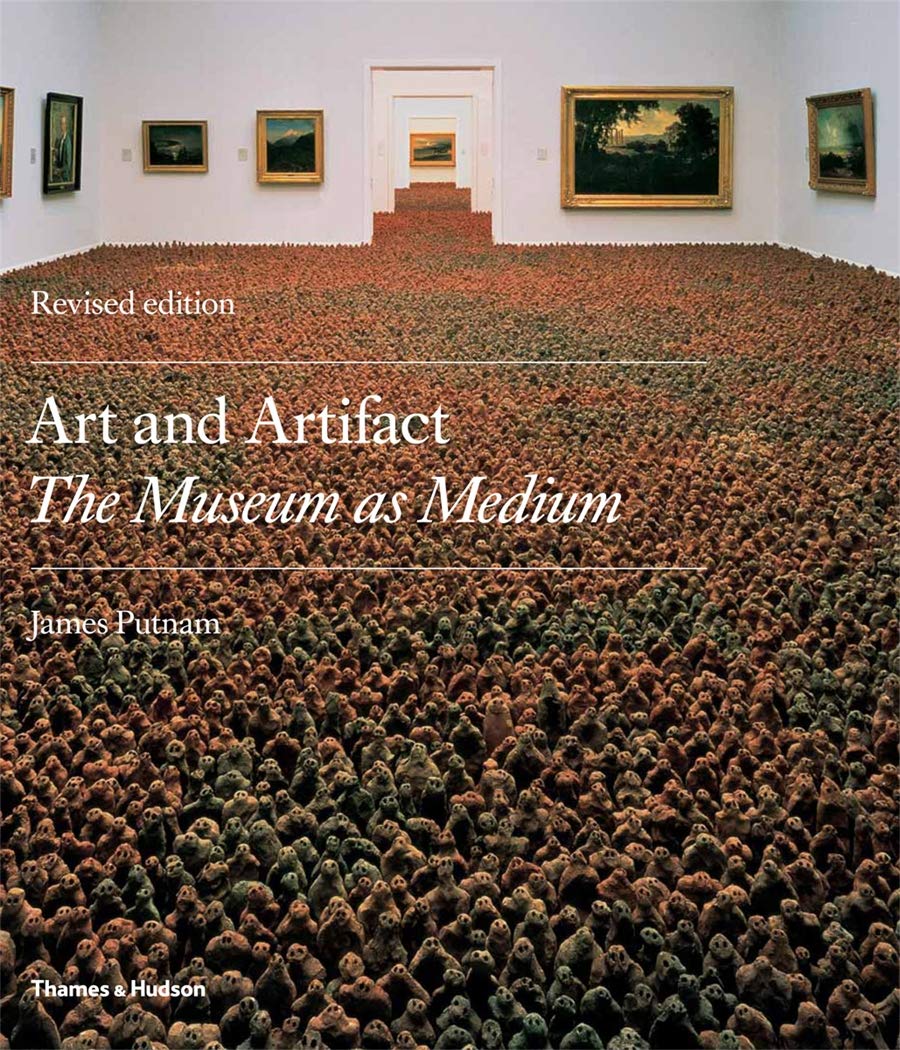

From Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Portable Museum’ Boîte-en-valise of the early 1940s to the latest interventions by artists in museums’ displays, merchandise and education, artists of the last seventy years have often turned their attention to the ideas underpinning the museum. Clark’s photographs hint at the emotional connections between curators and collections staff and “their” objects. Curators like show off their storerooms. Seb Chan writes about discovering strange things in museum collections: “That is part of the texture and nuance that museum insiders love — and some of the best museum experiences are those where you chance upon a particularly quirky or strange set of objects.” Museum sense is acquired by working with objects and collections. It’s more than academic knowledge. It’s more than collector’s expertise. It comes from hands-on work with collections: building them, handling them, the long, slow process of making sense of art, history, or nature from them, and of using them to connect with the larger world. In the Storeroom This is a vexed — and therefore important — time to be making a case for real artifacts and the skills and knowledge of curators. Museums are once again at a moment of revolution. Their position in the cultural landscape is uncertain. For some, their collections seem irredeemably tainted as colonialist. For others, the world of the digital and virtual seems more interesting than the actual and real.What I want to argue is that collections should remain an essential elements of museum work, but that we need to add to it a second kind of knowledge: connections. Collections and connections, together, are the foundation on which museums can build their future. But in the longer term, clearly not. He did not lay a foundation on which others could build. He created a museum that was unable to change with the times. He failed to teach his colleagues or his audiences about the value of the collection. Jenks was a good at curating, but not a good curator. He collected, but never connected.

Displaying art and artifacts — making exhibitions — is a skill that depends upon the curator’s intimate knowledge of the objects, their knowledge of context, and their connections to audience. A good exhibition is an argument from art and artifact, designed to communicate with its audience. Conversation Museums need both collections and connections. Curators need to collect, and connect. It’s the combination that give museums their power. CollectionsWe’re at a moment in museums where many people are proposing new roles for them, new social and cultural needs that museums might fill. What I’m interested in is how to fill those needs — how museums can be useful — in a way that takes advantage of their strengths — in particular, their collections and curatorial expertise. If we don’t — well, remember what happened to the Jenks Museum. One might diagnose the problem as Prof. Jenks’s inability to connect. In the short term, yes: he was knowledgeable, dedicated to his museum, a great collector and brilliant at convincing others to donate their collections. He worked hard at putting things on display and was serious about teaching. He believed deeply in the mission of the museum. Alongside this decolonizing critique, there’s a resurgence of material culture studies, under a new name, that might offer us a way out of conundrum of disconnected objects. Like the Lonetree and Bercaw critiques, it suggests that things are more complex, with more stories, than the Prownian tradition of material culture suggests. If we add to traditional curatorial knowledge — “museum sense” and connoisseurship — an appreciation of the living stories of objects, we get a new understanding of the complexity of artifacts. We can build on new scholarship that puts material things — and thus museum collections — at the center of culture and history. The challenges to traditional material culture studies re-enliven it, suggesting new ways to learn from things Connecting with Audiences Collections are what make museums unique. Museum collections are more than objects; they are carefully chosen assemblages, the product of a curatorial way of knowing. They are sustained by curatorial expertise. Curators have a distinctive way of understanding objects, making arguments with them, and telling stories with them. Otherwise staid and practical curators slip into poetry when they try to describe this ability to understand objects. George Brown Goode, the first director of the US National Museum, called it “that special endowment… ‘the museum sense.’” Others talk about “object-feel,” or “a good eye.”

Just as good collecting requires understanding context, so does the good use of collections. Using collections requires knowing what was collected, as well as what wasn’t. What’s missing, and why? It requires understanding of the context of collecting, and of the history of the collections. Collections’ history shapes the way we use them and the stories we tell with them. We need to understand collections’ connections — those that were broken, those that survive, those that might be reknit. Curators need to reconnect collections with communities. Thelma Golden, director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, offers a model for how to do this. The audience for her exhibitions, she insists, are not art historians, but the public. One of the secrets to the success of her exhibitions, she claims, is that she is not an art historian, but rather, a curator, someone who engaged with artists and their work. “I learned to curate from curators.” Her technique for designing exhibitions was simple. She moved the artworks around in the space until it all made sense. “I am someone who is totally experiential,” she told the Washington Post . For Thelma Golden, what’s important is the direct experience of the art, not “works, but works in space.” We might add, works in social space, that is, space with people and things. The first half of this essay explained the curatorial skills that allow deep connections between the curator and museums collections. That’s a necessary first step, but not enough. We define curatorial skills too narrowly defined when we limit them to collections. I want to expand the definition curatorial work to include all of the ways that collections might connect — with communities, with audiences, and with each other. Curators need to know how to make connections.

This book examines one of the most important and intriguing themes in art today: the often obsessive relationship between artist and museum. One important aspect of this knowledge comes from the curator’s physical connections with the objects. They have the objects, and privileged access to them. Whatever there is to an object that can’t be can’t be described or photographed or digitized — that’s a place to look for particular curatorial knowledge. Geoghegan and Hess offer this list of some of these qualities: “three-dimensionality, weight, texture, surface temperature, smell, taste and spatiotemporal presences.” This publication provided a brief overview of the history museums and how they have progressed in terms of exhibiting collections and art and how this gradually evolved from ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’ into the installation of avant garde art work. The book covered the various methods of how collections have been displayed in the past to signify importance and significance of the objects, such as, vitrines, plinths, drawer cabinets and specimen jars.

Related:

Great Deal

Great Deal